Cinema Year '25: August Discoveries

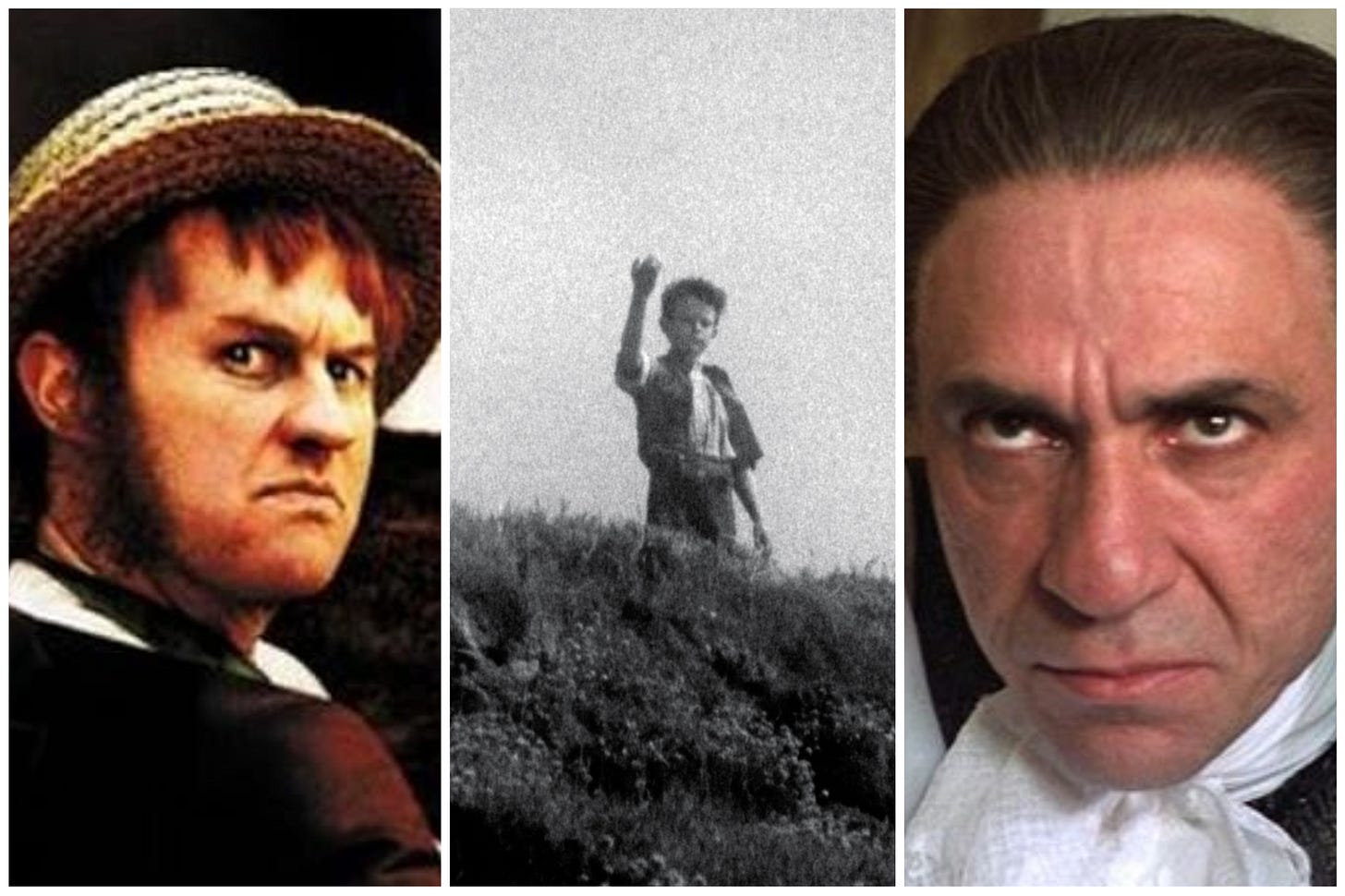

Amadeus / Arcadia / The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse

Welcome back to Cinema Year ‘25, a monthly review supplement. August’s discoveries took us from the peak of Viennese decadence, through a rural archival oddyssey, to the finale of British Comedy. Words by Jeremy Arblaster, Kirsty Asher, and Ben Flanagan.

Don’t forget to subscribe to receive this and more film writing direct to your inbox.

Did you attend an interesting repertory film event this month and want to write about it? Get in touch yearzerocinema@gmail.com.

Amadeus (Miloš Forman, 1984, USA)

In today’s era of internet democratisation, where the cultural cachet of critics and awards bodies has waned significantly, how much weight does the canon still carry Amadeus (1984), may first strike modern viewers as an intimidating watch. Culture with a capital C. Recognised with 8 Academy Awards (as well as being a healthy box office hit—imagine that!) the film is ostensibly highbrow stuff, telling the story of the rivalry between composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri during the 18th Century. And yet, highbrow it ain’t.

Soundtracked by Tom Hulce’s pitch-perfect cackle as a frivolous, fun-loving Mozart, the film wallows in the fictional gutter-beef between two egotistical men, with F. Murray Abraham turning in an Oscar-winning performance as the envious Salieri. Often deeply unserious, Amadeus leans heavily upon Salieri’s view of Mozart as an unrefined bumpkin, setting up a friction with the audience’s preconception of Mozart’s music as being for the elite.

But it’s Mozart’s passion and joie de vivre that stand out the most when viewing this for the first time, forty years on from its initial release. Was his music always destined to be for the people? From The Simpsons (1989–) to Trolls: World Tour (2020), years and years of decontextualised Mozart has somewhat confined the composer’s music to a classical ‘Top 40’, his genius loaned out generously, democratised via pop-cultural osmosis. And by accepting Amadeus as another pop-cultural artefact that borrows from Mozart’s greatness, its salacious fiction is all the more fun.

Yet as loveable as this film is, I felt a deep sadness at its close. My father, a lecturer and opera critic who passed away just over three years ago, should have shown me this film. As a gateway into the world of opera for those with... less refined ears, I wished he had. The films discussed in Cinema Year Zero’s ‘discoveries’ section are, by their nature, found too late, but this one stings just that little bit more. JA

Arcadia (Paul Wright, 2017, UK)

A burgeoning trend of understanding the British landscape through politics and culture has emerged in the twenty-first century. Arcadia, Paul Wright’s most recent feature to date, could be considered a keystone of this trend, in that it correlates familiar semiotics—British calendar rituals, the act of enclosure and its ripple effects, industrialisation, the Third Agricultural Revolution—into a grand manifesto of what was lost of Britain’s past self, and what can be regained of it.

Although reliant almost entirely on archival footage, (mostly from the BFI, which they happily tout on BFI Player) the film is bracketed by a quasi-folk tale of a young maiden in a glen witnessing the events unfolding in the archive. When first she is introduced through voiceover, the shadow of a man looms ominously over well-tilled soil. This same shadow is seen at the end as well, although it retreats, in a hopeful symbol of reforming and rejuvenating the much-bothered earth. Between these brackets, the maiden witnesses the devolution of the bucolic early twentieth century, with its familiarity and closeness, into the destruction of landscape in pursuit of capital, showing miles of felled timber, saws and diggers mercilessly felling trees. Following reenactments of eighteenth century enclosure, clips of illegal raves and the Battle of the Beanfield dance spikily in protest. Calls to rural resistance are harkened in footage of Beeching cuts protests and the Tolpuddle Martyrs festival.

Perhaps in 2017 this film read as an innovative narrative of what a leftist-progressive view of the British rural landscape can look like, but from a contemporary viewpoint, as engaging as the footage is, these semiotics are overfamiliar, found now in countless books in a Waterstones section and niche Instagram accounts. It’s a reminder that the web of meaning these images convey is fairly rigid, with little else to propel the movement forward. This in itself speaks to a halted cultural era that can only look backwards, even while regarding nostalgia with caution. Nevertheless, for those of a certain sentiment (i.e. me), it is an absorbing piece, acting in the mode of Ron Fricke’s Baraka (1992) and Samsara (2011) to engage both wholesome and troubling imagery in pursuit of touching on a hopeful and well-rounded human experience. KA

The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse (Steve Bendelack, 2005, UK)

We used to build things in this country. Bits of Hammer and Ealing and a whole wealth of British TV tradition, and theatre going back through panto and music hall. Bric-a-bracc’d together, The League of Gentlemen’s Royston Vasey is a sandbox to splurge

It may have been reduced in the culture to catchphrases, but the series is precise and elegant. And then the film goes further—by destroying itself.

Largely ignoring the characters who made it a phenomenon, like the snouted Edward and Tubbs, or turning a character like the perverse Herr Lipp into a Henriadian hero, The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse uses the larger canvas of a Universal/FilmFour production to splurge its four creator’s preoccupations wherever they may fit. David Warner fires on all cylinders as Dr Erasmus, whose efforts to create ‘an humunculus’ begin as a major aside, an alienating flight of fancy intended to infuriate catchphrase lovers, even as it engages in a glut of baroque production details.

That something with this level of in-joke folly and disregard for its own audience could even be made or released wide enough in Britain to be met with minor irritation, now seems like a minor miracle. The pages of Cinema Year Zero have sometimes felt like a lament for Jerusalem but really, it is remarkable. 20 years ago we had Winterbottom, the film council, and hope. Now we have no Hope, no Cash, and no heir to the classic British comedy crown. BF