Interview: Joe Bini

"It’s just a language: an image language. It shouldn’t be that big of a deal."

Welcome back to VOLUME 21: The Creative Nonfiction Film Weekend 2025.

Burden of Other People’s Dreams is an attempt to cross the experience of reading a book with the experience of watching a film.

Created by renowned film editor Joe Bini (Grizzly Man, You Were Never Really Here, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed), the piece explores the psychology of anonymity required in being an editor. Combining words and imagery, physical and digital media, it blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction to tell a story about how stories are told.

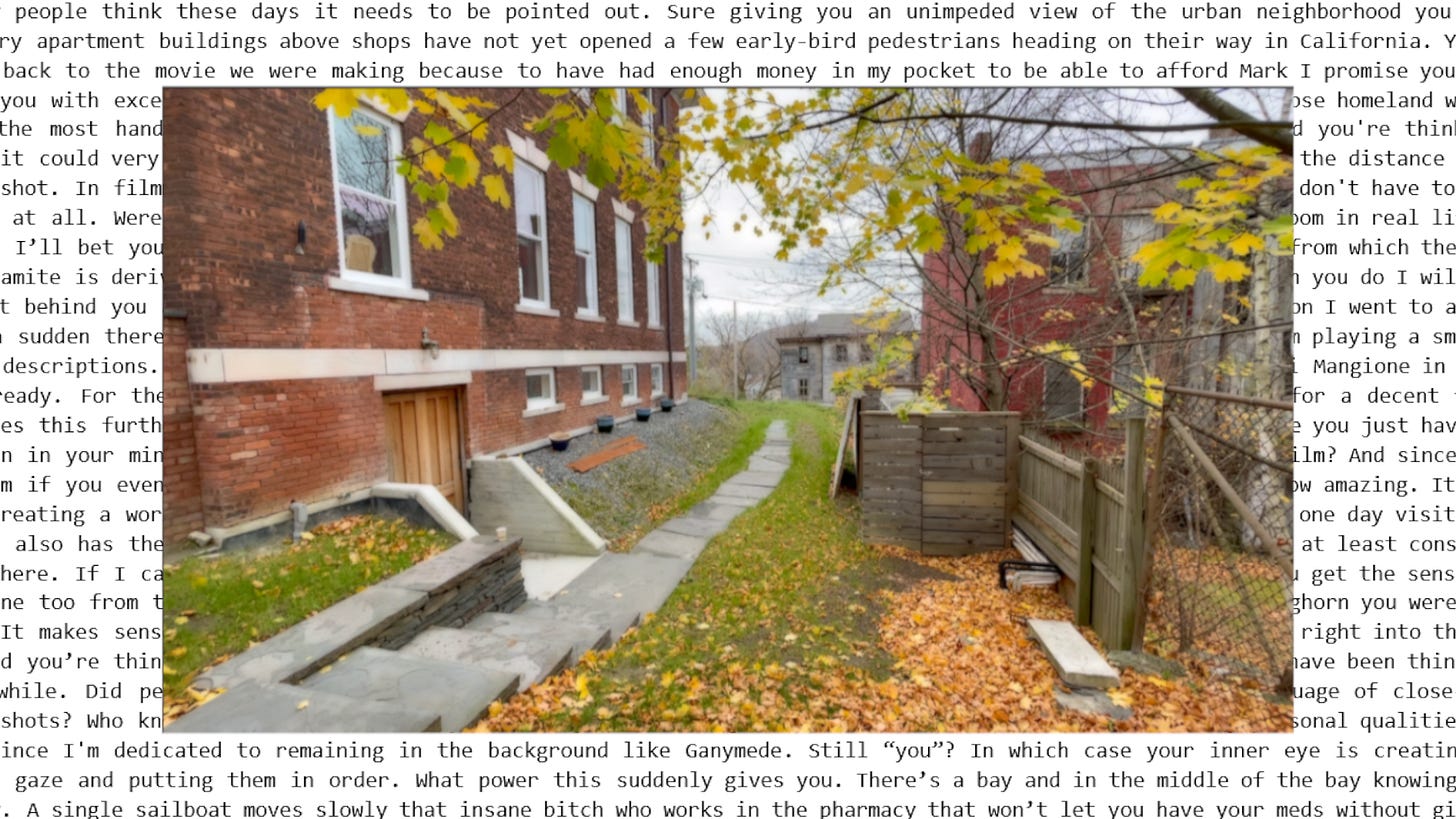

The piece was originally conceived as a digital book with embedded film elements, potentially in the form of an app. For its first public presentation, Bini created a ‘live’ version: an excerpt called ‘Book II: Ganymede’ that is designed to be experienced one audience member at a time.

The curators of CNFW are also the producers of Burden of Other People’s Dreams, including Orla Smith, who conducted this interview.

Time collapses in on itself at DNA Cafe next to the Rio Cinema, as I sit with an orange juice on a hot day, across the table from Joe Bini. As well as conducting this interview about the piece, we discuss the logistics of presenting Burden of Other People’s Dreams as a live piece. Flash back some years: co-producer Kimia Ipakchi, technical director Nick Bush, and I are teenagers in another coffee shop (Watford Starbucks, unfortunately), talking about making movies. In that naive time, ‘making movies’ meant something quite specific and financially burdensome, if done properly—it’s probably why we didn’t actually finish a film together until 2022. Now we are here, collaborating on a piece that is small—one room, one audience member, composed from found images on the internet and from Joe’s personal archive—but that makes the idea of ‘filmmaking’ feel so much bigger than it once did. As Joe says, ‘it’s just a language: an image language. It shouldn’t be that big of a deal.’

I laugh when Joe casually refers to his twenty year editor-director relationship with Werner Herzog as ‘a long internship’, but it’s also what makes his approach to artmaking a balm. Perhaps you’d think that a career should start with DIY experiments and end with making Grizzly Man (Herzog, 2005), but in this case it happened more or less the other way around. I suggest that many people would think this niche, difficult to finance (we’ll do our best) personal project is a step back career-wise—but it’s a provocative point rather than a question I actually need the answer to. To be honest, the relief I feel from realising that filmmaking and capitalism can exist separate from each other is immense. ‘I’ve always had this dream of being able to do film like a painter or writer does, where there’s nothing between you and doing it,’ he shares. It’s similar to something that Julian Castronovo (whose film Debut plays at the festival on July 5th) said in an interview with Filmmaker Magazine: ‘I liked the idea that I could be a filmmaker in a way that resembled having a studio practice, where I wake up, have these images that I want to make, and just try different things. If I mess up, who cares? I’ll just wake up and do it again the next day’. While Castronovo is at the beginning of his career, and Joe well into an incredibly successful one, they both found liberation in removing pressure and preciousness from the filmmaking process.

An inspiration for this new chapter of Joe’s life as an artist was his work on live cinema projects, which ‘made me think about different ways of presenting film.’ He co-directed the live cinema piece A Thousand Thoughts (2018) with Sam Green, and then later co-created the live cinema performance Little Ethiopia with his partner, editor Maya Daisy Hawke. It started when the couple were asked to give a lecture on editing at Falmouth University, and they decided to do something a little different from the typical career walkthrough. They each cut short films about their relationship, using footage they had available to them in their personal archives or on the internet. They had not seen each other’s films prior to the screening. ‘We would discuss basic parameters of what they should do. But then we tried to fuck with each other quite a lot with that.’ There were scripted bits of conversation in between the films, but ‘when we talked to people afterwards and asked what they liked about it, they said “You!” I didn’t realise they were looking at us while the films were on.’ They performed Little Ethiopia seven times between 2018 and 2020, and each time the films changed, as did their reactions. ‘One thing I like about live cinema pieces,’ Joe says, ‘is nobody knows what they are, so nobody has strong opinions about how they should work or how long they should be.’

This new context breaks some kind of boundary in the audience’s mind and allows the work to exist on its own terms. Burden of Other People’s Dreams goes further by adding the element of the written word—it was originally pitched to me as a sort of autofictional memoir about being a film editor—but Joe points out that writing has always been a part of his filmmaking. After all, for the time they worked together, the iconic Herzog narration was really an amalgamation of Joe’s and Herzog’s creative sensibilities, ‘a form of poetry… to do with the flow of imagery.’ There were large elements of pre-written text in the live pieces he’s co-created, as well, which were read out as a sort of narration. ‘I just really started thinking about, if you plant ideas in the writing, and don’t put them right on the imagery, will they linger? That’s a big question in [Burden of Other People’s Dreams]. And who is the audience? That’s another big question. I was starting to like the idea of the audience being more like a reader. It’s an interesting thing to pursue: as opposed to 300 people in an audience that you’re trying to all capture in the same moments, you have a [single] reader who reads at their own pace.’

‘When I started talking to Nick [who took on the role of technical director] about this idea, and we were talking about what this thing is, this app or whatever, I was asking all these questions, like, could it change after you’ve finished it? Nick was like, yeah, of course it could! And so in other words, it could have no end. The next time you pick the book up it’s totally different. Or it is slightly different. I just thought, wow, that’s amazing. It could be a container for everything I’ve ever wanted to do for the rest of my life.’ It’s a big thought, and an exciting one. ‘Most of my director friends spend two to five years developing a single film. I just can’t do that. I’ve tried. Maybe I could find a way that I could just do shit, and the only thing stopping me is the time that I can devote to it. Maybe there’s a new way of doing film. It all sounds a bit grandiose, but who knows! I don’t know. It could be.’