Notes from London Film Festival (II.)

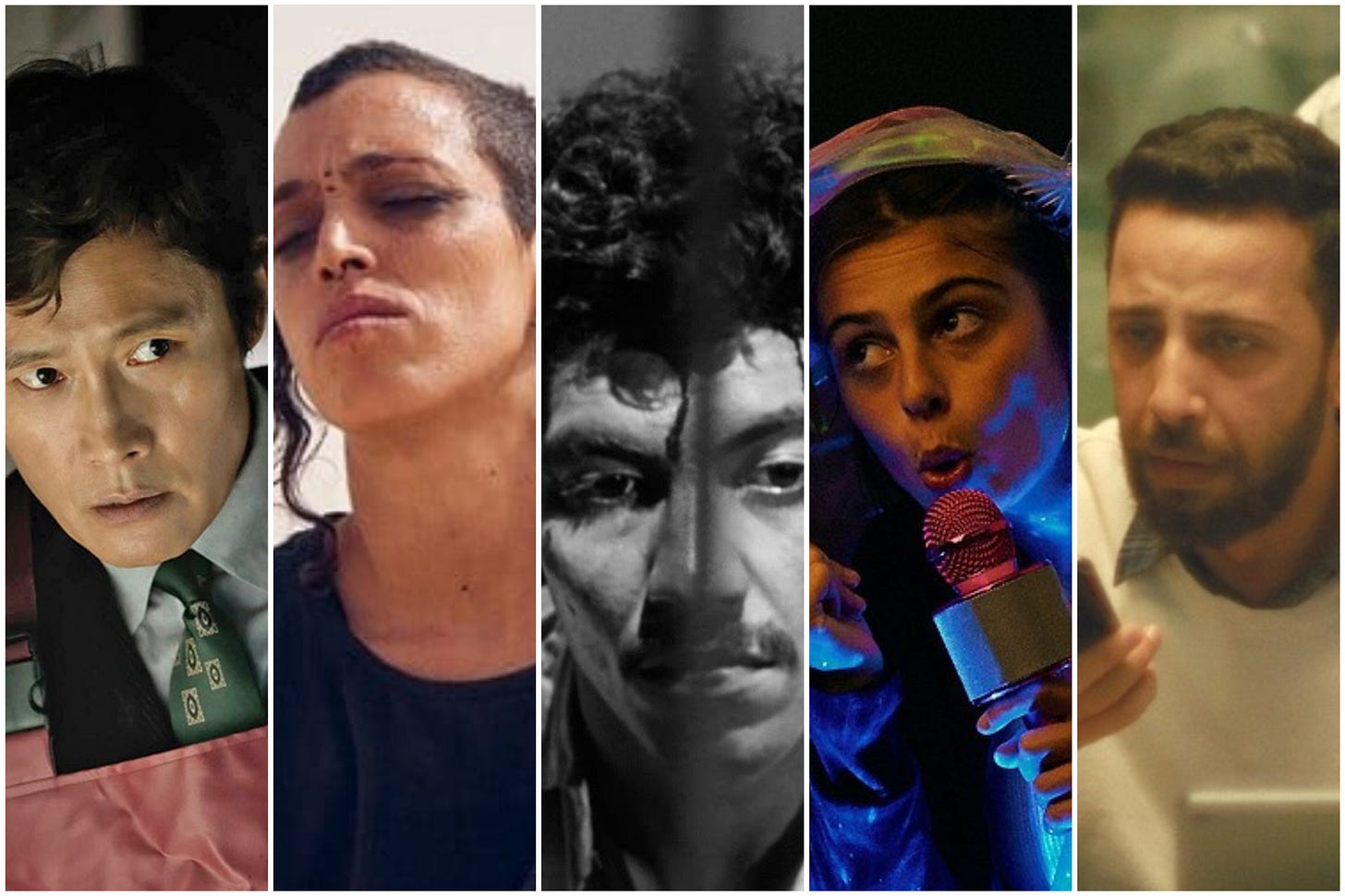

No Other Choice / Sirāt / La Paga / Fwends / The Voice of Hind Rajab

Welcome back to our coverage of London Film Festival 2025, presented across this week in three parts.

Today we get into the weeds of the programme with five reviews including festival favourites, rediscovered masterpieces, and borderline pariahs. Words by Alistair Ryder, Blaise Radley, Joel Whitaker Ben Flanagan, Phoebe Hadaway.

Read the first block of our LFF reviews here, and part III here.

No Other Choice (Park Chan-wook, Korea)

Heartbreaking – the worst person you know is also a victim of late-stage capitalism. Park Chan-wook’s satire, the rare festival circuit favourite to be ha-ha funny and not just chin-strokingly “amusing”, reunites the director with his Joint Security Area star Lee Byung-hun, who’s having the time of his life playing the odious corporate stooge Yoo Man-soo, who assumes toeing his paper company’s anti-union line for 25 years would keep his job safe.

But rather than make his lead an empathetic, tragic fool, Park – adapting Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax – keeps twisting the knife, making him even more detestable to the working class he’s unwittingly found himself in. He frequently refers to himself as “unemployed” when he’s too prideful to admit that he’s working in a warehouse. He’s so convinced that he’s the tragic hero of his own story that he hasn’t stopped to realise his problems are all of the first world variety: how can his children survive without their Netflix subscriptions and private music tutoring?

This obliviousness helps set the stage for an increasingly mean-spirited romp, as Yoo Man-soo embarks on a sloppily orchestrated killing spree of fellow paper industry veterans, as he assumes they are his rivals for the only job opening at a major conglomerate. The lack of method to this madness contrasts sharply with Park’s exemplary staging of even the most incidental sequences, arguably opening himself up to criticisms of over-directing every last scene. Even though the results are dazzling enough to silence any dissenters, at least in the moment. In another filmmaker’s hands, you could imagine this playing out like a straightforward Coens-riff, but Park pushes past Fargo-esque dark comedy about incompetent criminals into pure Mr. Bean territory. And that’s exactly how this oaf who doesn’t know how good he has it deserves to be treated. AR

Sirāt (Oliver Laxe, Spain)

It’s an autumnal Monday evening at the BFI IMAX, and a middle-aged Spaniard with long flowing hair stands before a packed crowd. By the emphasis he keeps putting on “bodies” and “feeling” you’d think he might be introducing some sort of tantric sex retreat—but no, Oliver Laxe is in London for the premiere of his film Sirāt, having won the Jury Prize back at Cannes in May. And yet such accolades (or even being liked) aren’t what Laxe cares about, or so he says—he just wants the whole audience to feel Sirāt on a visceral level.

Not to sound like I’m farming pull quotes, but it’s hard to discuss Sirāt without simultaneously deflating much of the joy of experiencing it, in part because it does incur such strong bodily reactions. Only a few films at LFF this year were scheduled at the IMAX (wedged between empty showings of Tron: Ares), which begs the question: why Sirāt? Certainly, its wide tracking shots of trucks tearing through the desert aren’t reformatted for the tall, boxy screen. And while Kangding Ray’s thumping techno score is no doubt a factor, reverberating the seats from the opening frames, the real answer is a simple one: in IMAX, try as you might, there’s no escape.

If that makes Sirāt sound like a high-octane thriller, it is in part. The central mystery—which sees non-raver dad Luis (Sergi López) searching for his daughter amidst sensuously writhing crusties at a Moroccan-located, European-populated free party—certainly lends itself to more traditional narrative tensions, not least during the cliffside trucking sections which playfully crib from The Wages of Fear (1953). But it’s also something much stranger and repeatedly baffling, a film concerned with existential themes like purgatory and salvation on the one hand, and cartoonish melodrama and comically-timed explosions on the other. As Laxe hoped, it does frequently transcend simple considerations like “good” or “bad” to become something wholly other, akin to a metaphysical theme park ride. All that’s to say: go watch this one with your friends. BR

La Paga (Ciro Durán, Colombia/Venezuela)

When we think of South American cinema from the 1960s, what do we think of? My mind is usually drawn to the rapid montage of Santiago Alvarez, the radical experimentalism of Solanas and Getino, and the brutal formalism of Glauber Rocha. But how did we get there? How did such a violently distinct style - with a matchingly powerful political voice - emerge across a continent? This is a question far beyond the scope of this review, but Ciro Durán’s La Paga offers as interesting a starting point as any.

Released in 1962, the same year as Glauber Rocha’s first feature, La Paga is the story of a peasant farmer struggling to provide for his family. The film takes inspiration from the Italian Neorealist movement that had made political waves across Europe–its influence spreading through to the Soviet Union and thereby becoming in vogue globally for those seeking to free themselves from their capitalist colonial overlords. As the film progresses, our protagonist begins to dream of a world in which he is brave enough to act on his frustrations.

These sequences are much more powerful than the moments steeped in social realism, they hold a distinctly Eisensteinian flavour: characters become symbols, our most radical dreams realised. Towards the end of the film this is curtailed by a return to brutal reality. This feels poignant for La Paga’s place in South American cinema–reaching for radicalism but not quite yet having the scope or a flourishing movement within which to act. Things would soon change, and La Paga is certainly a stunning beginning to an extraordinary cultural moment. JW

Fwends (Sophie Somerville, Australia)

Taking the point and shoot manifesto of Breathless to the despondency of our late-capitalist hellscape, Fwends is positively brimming with spontaneity. That’s how Em (Emmanuelle Mattana) would see it, anyway. She’s a reluctant yuppy who arrives in Melbourne for a weekend hang with once-bezzie Jessie (Melissa Gan), herself freshly single and lapsed into a weed funk. They float along, with the merest wisps of plot motivating arcs of minor self-discovery.

The opening 20 or so minutes, in which the pair march around the city in search of coffee, is a wonderfully choreographed dance. They writhe around like snakes, each sizing the other up. Director Sophie Somerville captures long takes shot on telephoto lenses, almost always from way down the block, the camera panning and zooming like crazy to keep up with their half-formed jokes and developing bits.

When they end up playing in Jessie’s apartment with a load of coloured mesh, things become psychedelic. Wearing facemasks, they lean over her balcony with the material flowing below them, so they look like mermaids as Em delivers a bleak monologue on sexism. They make a mesh tent, and goof around until it becomes stale, even for them. The camera doesn’t blink.

Things eventually take a more serious tone, as their endless chats become more and more claustrophobic and force them to open up, even if they don’t want to. A clown they meet in the street becomes their only respite. As passersby take photos of the film shoot or stare down the camera angle, you may even think of Rivette and Co’s freedom of invention. Or you’ll think of how this grounds the co-leads, who pull Melbourne into some kind of space akin to citybreak Dreamtime. BF

The Voice of Hind Rajab (Kaouther Ben Hania, Tunisia/France)

There’s an episode of Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom where Jeff Daniels’ renegade newsman (who says it like it is because the news is important godammit!) clashes with his producer, a quintessentially spineless bureaucrat who believes that no matter how important the news, procedure is more important. Daniels’ character stresses that it’s important to do the important thing (the news!!) while his producer whines about the minutiae. When I sat down for the midday screening of The Voice of Hind Rajab I was not expecting it to have this same structure.

It takes place during the 18 hour period where Palestinian Red Crescent workers are on the phone with Hind Rajab, a five year old Palestinian girl who has been surrounded by the IDF, trapped in a car with her already massacred dead cousins, aunty and uncle. The film’s key formal device is that actual voice recordings of the incident are used verbatim. Including Hind Rajab. There’s no doubt that this is emotionally affecting, but Kaouther Ben Hania’s rote dramatising doesn’t exactly do the truth justice.

Omar (Motaz Malhees), a Red Crescent phone operator, pushes his higher up Mahdi (Amer Hlehel) to dispatch an ambulance ASAP and be damned with bureaucracy. Its formal sop to realism glibly bypasses Mahdi’s interiority. Somewhere between the two is Rana (Saja Kilani), generic and motherly. She’s the empathetic and pure woman left to take on the emotional weight while the men act erratically. In one of the many scenes where Omar and Mahdi are arguing, Rana shoves a photo of Hind between them, which feels particularly insulting in its heavy-handed and phoney symbolism.

To warp an active genocide to fit such a standard, soulless Hollywood shape, can only be diminishing. Specifically toward Hind Rajab herself and her mother who, despite all the big names whose names are tied to this project, is still living in Gaza with no material support from Pitt or Phoenix or Cuarón. Through a strong singular example, the film is less a biting confrontation of the realities and constant mourning faced by Gazans, than an exploitation of the community for awards circuit buzz.

On September 6th 2025, Hind’s mother Wissam Hamada’s neighbourhood was surrounded by Israeli tanks. She issued an urgent plea alongside asking for financial support; “I am begging every influential person, every celebrity, every connection to save me. [...] We must leave but we have nowhere to go… I want to live, I want to protect my family. Please save us”. It doesn’t seem like any amount of acclaim will do anything to help, nor will a critique of that so-called activism. PH