A Bunch of Amateurs: an interview with Matevž Jerman

“It's alternative film!” – “No, it's anti film!”

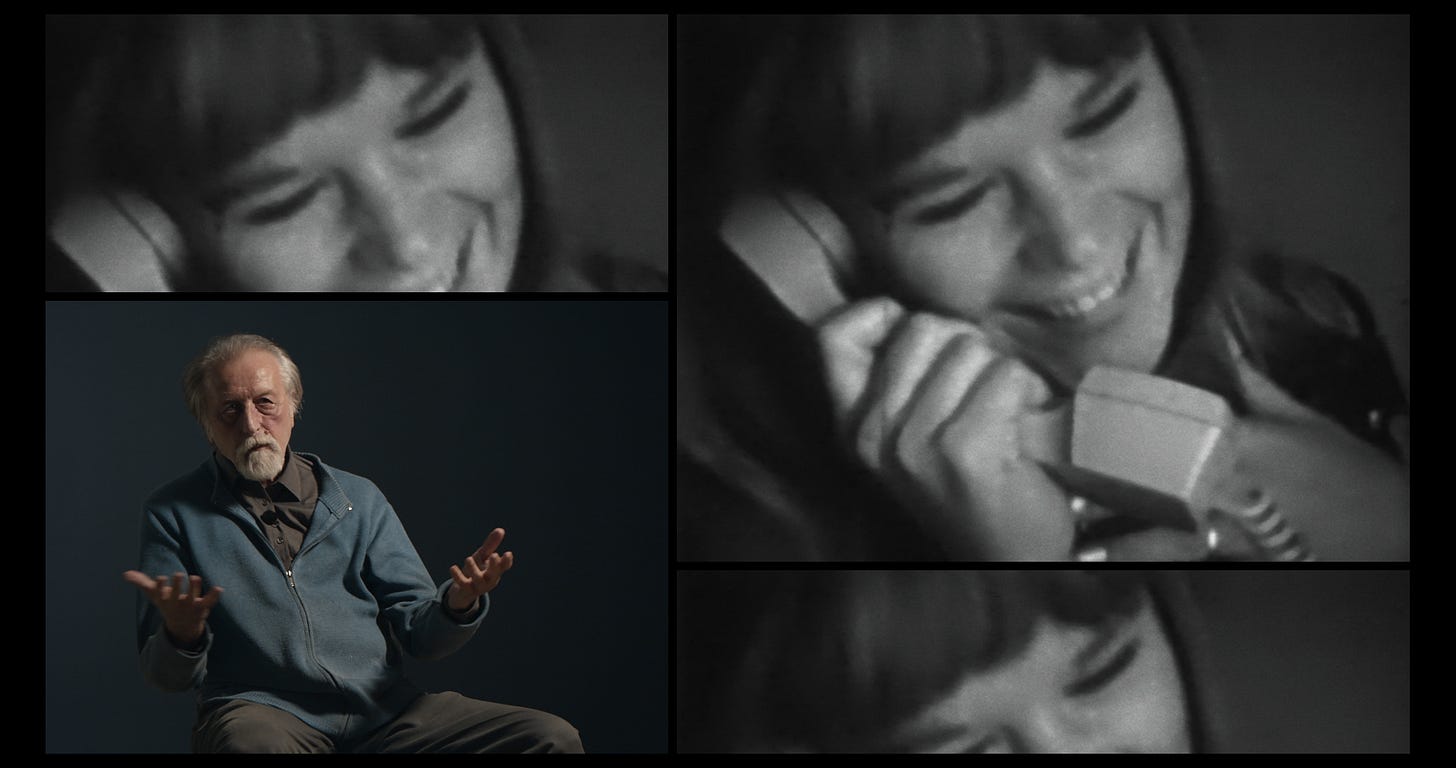

As a Yugoslav republic from 1945 until its independence in 1991, Slovenian cinema was often left in the shadow of its bigger brothers to the east, Croatia and Serbia. But the experimental cinema which emerged there was as thrilling, liberatory, and exciting as any in the region. This experimental scene is the subject of Alpe-Adria Underground!, a documentary directed by Matevž Jerman and Jurij Meden, which recently screened at Cinema Rediscovered alongside a selection of the experimental shorts. The documentary is a roving account of the country’s avant-garde film scene, starting from its beginnings in the 1950s, its widespread growth through the cultural explosion of the ‘60s, all the way up to the shift towards tape and video art in the 1980s, aided by acres of restored footage, interjected with the talking heads of a grizzled crew of critics, curators and filmmakers from the former Yugoslavia.

Alpe-Adria Underground! emerged partly in tandem with a digitisation and restoration project alongside the Slovenian Cinematheque. As co-director Matevž Jerman explains during our chat ahead of the Cinema Rediscovered screening:

“The funny thing is that the sole process of producing this film really accelerated the digitization and restoration of this whole body of work of experimental cinema. Because if we were to be waiting for some official funding, if you decided to make it a project to digitise the avant-garde films, I think we would have to wait years and years.

And actually, the film was kind of an excuse, so we digitised 170 short experimental films to be able to include them in the film. Then we have perfect 4K scans, so we can work on restoration afterwards. The project of the documentary developed into two big projects. One is the film and the other one is the digitization and restoration of the films that we talk about and many others.

And regarding the restoration, it's a bit different compared to restoring 35mm films, which they often make them mint clear and remove everything to emulate the first copy with the colours and no scratches. We decide to leave these traces of the life of the small formats1, because usually there was only one copy of the film which travelled festivals and maybe after one or two screenings there were already some scratches and dust which means that the film was never seen in a perfect version. So we decided to not digitally remove scratches and stuff like that. We tend to be really minimalistic with the restoration work so that even the digital copy shows the life of the reel of the film.”

Yugoslav cinema has, since the country’s violent implosion in the ‘90s, remained largely terra incognita. Films (and filmmakers) feted in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s were suddenly forgotten, both by Western critics and cinephiles confused by the cosmopolitan, consumerist society captured on Yugoslav film compared to the chaos and murder on their TV screens, which they had been told were the result of ancient tribal hatreds; and by domestic figures seeking to forge new ethnonationalist political paradigms which erased Yugoslavia’s multiethnic context. The Yugoslav screen’s ‘dissident’ heritage, represented by figures like Lazar Stojanović, Želimir Žilnik or Lordan Zafranović, didn’t fit the new nationalist paradigm; they mostly criticised the old Communist state from leftist positions, so what’s the use of them for your ethnonationalist nation-state building project?

Critical laziness too plays its part, with its tendency to pitch Communist Eastern European filmmaking as an endless battle between liberal, freedom-seeking auteurs against authoritarian, humourless state bureaucrats and censors. The truth is a lot more complicated than that, revealing a constant negotiation and renegotiation between filmmakers and institutional figures (many friendly, some not so much) between what is possible and not possible. The Yugoslav kino-club movement is a one such example of the constantly shifting ground, and one seldom discussed by historians and film critics.

Ravaged by World War II and without a pre-war film industry to rebuild, Yugoslavia started the process of constructing an industry from scratch. The socialist state led by Josip Broz Tito believed in Lenin’s maxim – as all socialist states did – that “of all the arts the most important is the cinema”. The top-down approach created film studios in each republic in Yugoslavia, with personnel trained (often abroad) in the technological aspects of film. But from the bottom-up emerged kino-clubs, analogous to something like the film societies sprouting up in the West in the ‘50s; these clubs provided technical resources and workshops for amateur filmmakers to (as we say in the modern parlance) ‘fuck around and find out’.

“The Kino clubs were part of this big umbrella called the ‘ljudska tehnika’, [The People’s Technique]. The idea was to make art available for everyone. So you had not only Kino clubs, you had clubs of radio amateurs or you had clubs for photographs. Kino clubs would make equipment available for everyone, and I think one of the early ideas was that they would document everyday life or some social reality of the time…And then people would make their home movies with equipment available or they would make some fiction films, copying what they saw in cinema. In Yugoslavia they could see all the contemporary art house production from all over the world. The French New Wave was available in cinemas straight away. The New Hollywood films were screened.

Among all of this, there was some conceptual stuff that we can now belatedly recognise as experimental cinema, but for many, many years, all of this production was labelled as amateur cinema. So it was independent and because of this independent nature, no institution would take care of these films. This is one of the reasons why in Slovenia there is a gap of a couple of decades when these films were sank in a swamp, forgotten. Only in the 2000s did we start to rediscover them. Because of this label, ‘amateur’, and also because Yugoslavia didn't have a common agreement on what to call these experimental films, in Zagreb they would call it anti-film, in Belgrade, alternative film.

It was all a big mess in this sense, especially in Slovenia. At least in Zagreb and Belgrade, they had theoretical schools behind it. For example Mihovil Pansini in Zagreb was one of the main theoreticians and he organised GEFF [Genre Experimental Film Festival].

That the terminology consigned these films to the dustbin for such a long time is illustrative of restrictive language can be when discussing film, with a whole section of Alpe-Adria Underground! devoted to talking heads debating what the right term is. Terminology debates are part and parcel of Yugoslav historiography (cultural and otherwise) and are largely really fucking boring2 but, as Jerman acknowledges, it had a material effect on how these films were received.

"Especially in the case of calling them amateur, it really impacted how these films were treated throughout the years. But if we talk about how to label these films, I think the discussion about terminology is more interesting than the result that would come out. It's really funny how, even now, some authors or theoreticians that were already active in the ‘60s and ‘70s are still arguing. For example, a couple of years ago, in Alternative Festival in Belgrade they were still insulting each other and calling each other names: “It's alternative film!” – “No, it's anti film!”

But for the sake of discussion, I think the easiest way is to label them as experimental, because then anywhere in the world you go, everyone would know what you're talking about.”

With access to cameras, editing and lab equipment, young filmmakers could start to understand the mechanics of filmmaking. Most major cities in Yugoslavia had a kino-club, and by the ‘60s many former ‘amateurs’ were becoming increasingly professionalised. Any list of major Yugoslav filmmakers from the ‘60s onwards would be comprised of a majority of kino-club alumni.

“The kino clubs were a really nice breeding point where many film makers emerged like Dušan Makevejev, Slobodan Šijan, Karpo Godina. Many of the people who started in kino clubs switched into professional filmmaking.

The kino clubs would allow all this freedom and playfulness because they answer to no one. And also, if you give a bunch of kids a camera great stuff will come out because they're just fucking around.

Almost every city had a kino club and small festivals where these films were screened, but there were some major ones, like GEFF in Zagreb or Mala Pula in Pula, or the Festival of Short and Documentary Film in Belgrade. And they would screen these amateur films and then the film makers would get to meet each other and those that were already standing out at the time or winning awards somehow also clicked or connected. And I think there’s really funny proof of this: I saw a photo from 1968 from the Festival of Short and Documentary Film in Belgrade. The winners are standing on the stage with their plaquettes or something like that. And then you see Karpo Godina standing next to Želimir Žilnik who is standing next to Lordan Zafranović, but they didn't know each other at the time. They probably just met on that stage and one year later, Early Works was already made3. They met and they formed some networks or collaborations. So maybe the whole Black Wave in a way emerged from the activities that were possible in kino clubs.”

Beyond their relevance to the hard-hitting rawness of the Black Wave, the kino clubs also provide a direct link to the most mainstream and populist forms of Yugoslav filmmaking. One of the regular talking heads in Alpe-Adria Underground! is Slobodan Šijan, a Serbian-born director who emerged initially as an experimental filmmaker and talks at length about how many of the Slovenian experimental films highlighted in the doc influenced him. Šijan then went to direct Who’s Singin’ Over There (1980), The Marathon Family (1982), How I Was Systematically Destroyed By Idiots (1983) and Strangler vs Strangler (1984): four of the most enduringly popular and hilarious comedies from the former Yugoslavia4.

“I cannot compare [Šijan’s] early experimental films with his legendary features, but there's a level of freedom and playfulness that experimental filmmaking, or even the small gauge formats like 8mm camera, would allow for. It fixes a different direction in terms of thinking about filmmaking, probably more than some formalised education where you learn the laws of film language and so on. I think that [Šijan’s] starting point in experimental film would open his view of what could include in his features. And I think it's really important also to screen experimental films at film schools, but this almost never happens.

This should be the first thing that you see when you come to film school, then you see that film is a really open thing, not just the classics that we know. So I think this head start in experimental film might have something to do with the success of his films.”

The films that Alpe-Adria Underground! highlights, and the accompanying set of shorts screened at Cinema Rediscovered provide a brief but tantalising glimpse of the possibilities of this cinema. The hippiefied psychedelic drug trip of Karpo Godina’s Fried Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk (1970); the pure texturality of Davorin Marc’s Everything is Spinning (1978); the hypnotic dizziness of Dislocated Third Eye Series – Bismillah by OM Production (1984), ostensibly directed by a Sulejman Ferenčak but revealed to be a pseudonym for an anonymous filmmaker who created numerous films under an array of pen names. The programme covers films from 1965 to 1984, the doc collecting a much wider range of dates. Over that period, the importance of technology becomes clear.

“There is also a step forward because some of the films are from late ‘70s, early ‘80s when the kino clubs weren't that fashionable anymore, because the new generations had stepped up. Then the hippie psychedelia would have its moment and they didn't really care about institutionalised work. They wouldn’t work under the kino club umbrella because Super 8 cameras became available, which were even cheaper. The cameras were made, I think, in the Soviet Union or East Germany. So maybe the necessity of kino clubs became obsolete.

The curated programme actually follows the whole development from the early kino clubs to the early ‘80s, when video art would start to appear, and people made independent stuff under the umbrella of societies that were already really subversive, with the punk movement coming up, and in Slovenia there was already a big LGBT+ movement in the ‘80s, and so on. It was really progressive.”

One consistent thread is how remarkably liberated these films appear, even against the apparent grey of authoritarianism. Yugoslavia’s cultural history can be summarised very bluntly by periods of openness and periods of closedness, but this doesn’t necessarily hold up to scrutiny. Vinko Rozman’s Prague Spring (1969), one of the shorts highlighted here, very frankly confronts the aftermath of the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, contrasting images of Prague with newspaper clippings from Slovenia and contemporary speeches. Even that stands in contrast to the experiences of feature film directors: Aleksandar Petrović’s It Rains in My Village (1968) and Žilnik’s Early Works both touched on the Soviet Invasion and faced criticism where Rozman, seemingly, passed without notice. Did the experimental and ‘amateur’ nature allow for more freedom of political expression?

“Well, speaking about censorship, because people tend to portray this period and the whole socialist system at the time as super grey and totalitarian. But I think the films speak more about this really colourful, vibrant and free approach to different topics, to subversiveness, to filmmaking’ there's a lot of playfulness and joy as well. Censorship of course existed in some ways, but then I cannot imagine a totalitarian country would produce films such as Early Works; or The Role of My Family in the World Revolution (1971) or Life of a Shock Force Worker (1972) both by Bato Čengić; or Karpa Godina’s About the Art of Love or a Film With 14441 Frames (1972) which were financed by Zastava, which is the Army’s production unit. And then he made, y’know, a ‘fuck you’ film about making peace and love, not war. And in a really funny way.

Yugoslavia was kind of proud to screen these films around, maybe to save face or to present itself as a really open country, but sometimes, some films wouldn't be distributed. There's only Lazar Stojanović who was actually imprisoned, and the reasons behind his imprisonment might not have been the film itself. I think it's an ambiguous situation, but the level of subversiveness in the Black Wave years, it's crazy, don't know which country can you compare it to? In the Soviet Union films like this wouldn't be produced.”

One reason why Yugoslav cinema was able to thrive so resolutely in this period is its devolved, decentralised structure. As mentioned earlier, each republic had its own professionalised film studio, but from the point of view of the experimentalists and amateurs the access to resources was also decentralised to a Republican level. The effect was that each Republic had regional differences in their local film scenes.

“We had several bubbles. Epicentres like Zagreb and Belgrade, which organised big festivals and had a strong theoretical background behind their movements. And as mentioned Mihovil Pansini, for example, coined the term ‘anti-film’ and then wrote a manifesto about what film should be and how it should be thought of and made and reflected. And then, again, you had the school of Alternativni Film in Belgrade with [Tomislav] Gotovac5. They would play more with narrative film but try to change it. Maybe Šijan is also the product of that. Compared to them, Slovenia had no big… there was no theory behind it. So everyone was just doing their own thing, playing around and working really independently. They wouldn't mingle or have collectives or stuff like that. So in Slovenia, the films are really different from each other.

There's one thing that [curator and filmmaker] Ivan Ramljak sees as specific to the Slovenian experimental films, is that they have a strong sense of humour in the way they approach different topics. Compared to Croatian films or films in Serbia at the time, which took everything more seriously because of the theoretical background and manifestos.

So Slovenian cinema was even more free in the way that you could approach it. There’s really a lot of nature in all of these Slovenian films. They were really psychedelic, some of them. Because Slovenia was bordering with the Western world, Italy was in the grasp of your hand, a lot of interchange was happening really fast. You could buy records and watch films, so it was bursting with new trends that would then slowly go to Sarajevo or Belgrade and so on. Especially music, with the rock or punk scene, industrial music too, you always started hearing them first in Slovenia then it spread to the whole Yugoslavia. So that might have something to do with the approach of experimental filmmaking in Slovenia.”

What ultimately emerges from this brief snapshot is a counternarrative to the idea of grey, dull socialism. Within the Yugoslav republics there was a vibrant, roving artistic community. Its existence and flourishing was down to the creativity and imagination of its participants, but their flourishing was only possible because of the conditions laid down for them, which arose from a belief that everyday people deserve access to artistic tools. The apparatchiks who first set up the kino clubs in the 1950s could never have imagined that the chain of events would have led to Fried Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk. But that’s exactly what happened – and that is no accident.

Most of these experimental films were made on smaller-gauge formats, 16mm, 8mm, Super 8 and so on.

There’s a whole long-standing debate about whether New Yugoslav Film and the Yugoslav Black Wave are two separate strands, two nesting strands (with the Black Wave as a subsection of New Yugoslav Film), two interconnected strands, or the same thing. If you want my stance, I label it all Black Wave because a Black Wave sounds cooler than a New Wave. Every country has a New Wave – so who gives a shit about yours?

Želimir Žilnik’s 1969 feature film debut; it featured Karpo Godina as cinematographer and won the Golden Bear at Berlinale.

Quotes from Who’s Singin’ Over There and The Marathon Family remain part of the cultural lexicon.

Zagreb-born filmmaker and performance artist who moved to Belgrade, played the leading role in Lazar Stojanović’s Plastic Jesus (1971)