VOLUME 20: Ken Russell’s History of the World

Cinema Year Zero is excited to announce Volume 20: Ken Russell’s History of the World, a 7-essay retrospective of the untamable British director.

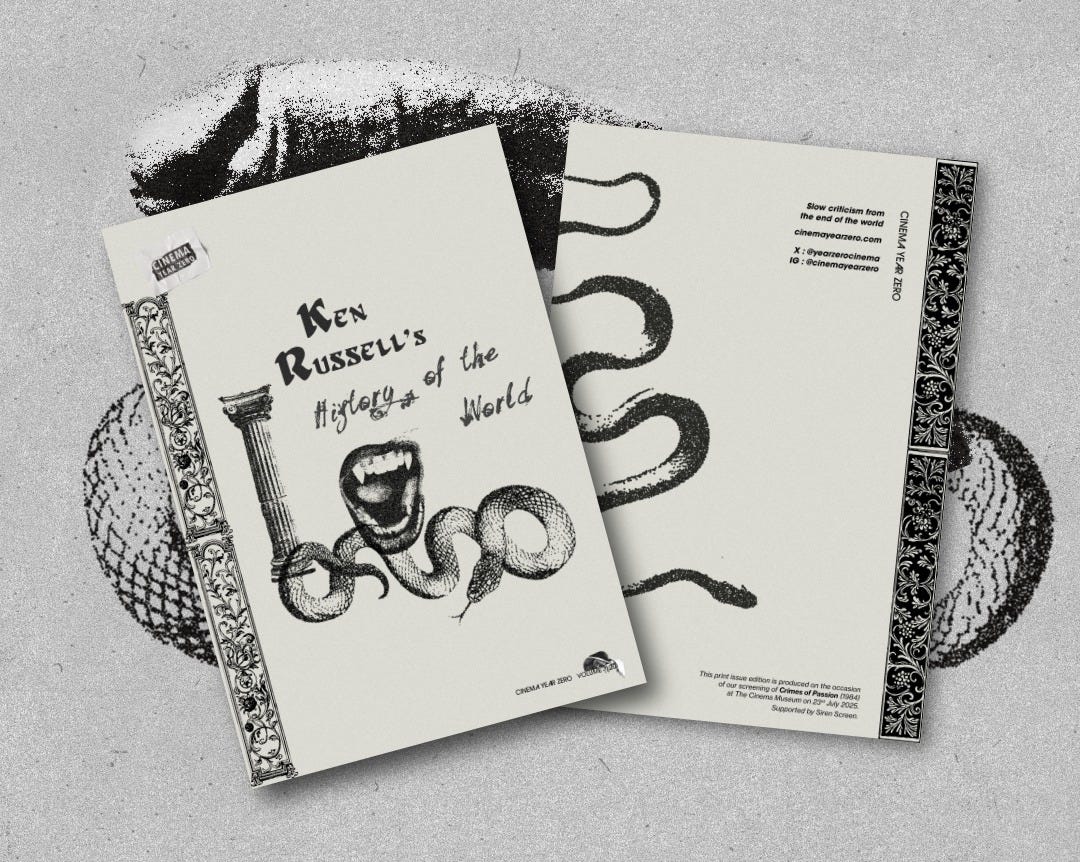

On 23rd July, join us at The Cinema Museum for a rare screening of Crimes of Passion on 16mm, where print copies of the issue designed by Jeremy Arblaster will be exclusively available. Tickets are now on sale here.

The event is presented in collaboration with film club and contributor Siren Screen, who have chosen a feature and short film both exploring the Madonna-Whore myth and the surreal world of bedroom fantasies.

But first, please enjoy the issue intro, penned by Cinema Year Zero Associate Editor, Kirsty Asher.

In the beginning, there was the word and the word was Ken. And he said, “Let there be bikes!” and there was a bike. Ken Russell’s career kicks off with the five minute short Knights on Bikes (1956), and as Ken’s career is born, so his first steps are taken by reimagining the birth of commercial cinema, making a silent film in an alternate Middle Ages where knights are hapless idiots riding boneshakers.

There is little of interest for Ken between this Dark Ages bouffonnerie and the 17th century. The High Middle Ages had plenty of nuns to be sure, some of them absolute fire, but it takes the Early Modern era dying and the Enlightenment struggling to be born to create sufficient Rabelaisian chaos, as is found in The Devils (1971). Here Louis XIII of France is the realest queen at the Ball and chalk-faced nuns run riot within Derek Jarman’s monochrome horny jail of their merciless God. Ken cleverly deduced that the only vessel through which a bunch of chaste nuns might lose their shit is the barrel-chested sexhouse we call Oliver Reed. Most importantly though, Ken also realised what Lowenthal knew to be true in The Past is a Foreign Country (1985), that “All accounts of the past tell stories about it, and hence are partly invented.”

For Ken saw in the stories of the past a means of depicting visions recounted in annals but witnessed only by their originators. Such visions: fantastical, horrifying, erotic, and given a cinematic lease of life that embodies their alluded surrealism. For it is now the 1810s, and the Romantic era is in full swing, and in Gothic (1987) the Shelleys and John Polidori join Byron at his Swiss mansion on the lake for a weekend polycule gone awry. In Ken’s Romantic era nipples have eyes, suits of armour have alarming metal dongs, and vampires adore menstrual blood. All the fascinating nightmares and neuroses that inspired unforgettable works of art of the era are laid bare.

Ken realised that despite the restrictive morality of the nineteenth century, the celebrities of their day are all about sex. For how else would one introduce Franz Liszt to a 1970s audience than with Roger Daltrey snogging a woman’s tits to the ever quickening beat of his jewel-encrusted metronome? Such a phenomenon as Lisztomania (1975) can only be reimagined for the screen with Daltrey and his louche Cockney rock star accent, sporting his “fantasticated gear” courtesy of Shirley Ann Russell. At the other end of the scale, Tchaikovsky battles his own metronome, his undeniable homosexuality beating against the hard rhythm of his sex-obsessed wife in The Music Lovers. (1971) A mere year before Tchaikovsky’s woeful death, in 1892, a disgraced Oscar Wilde descends into a male brothel with Bosie Douglas to witness Salome’s Last Dance (1988) courtesy of a scullery maid called Rose and the business’s own harlots. There, Bosie’s John the Baptist attempts to resist the seduction of Salome while subjected to some BDSM whipping from a bare-breasted woman in a black corset, all for the pleasure of dear Oscar, the sole audience member.

The twentieth century begins on a more mournful note, with the muted solemnity of Robert Powell’s Mahler (1974) in his final days, and the death of Rudolf Nureyev’s Valentino (1977). D.H. Lawrence’s bisexual panic is played out in languorous ardour in Women in Love (1969) and The Rainbow (1989). In the 1960s, the USA readily financed its depiction as the villains in a world where their Billion Dollar Brain (1967) supercomputer must be stopped from crushing Communism. Crises of control and the fragile power of the human brain reach their zenith in the MKUltra panic of Altered States (1980) and the New Age wonders of Uri Geller’s Mindbender. (1994) Then, the blessed Messiah returns in the form of Tommy (1975) to inexplicably drown Ann-Margaret in a vat of chocolate. The Hooray Henries of the 1980s are distilled into their most powerful totem, Hugh Grant, and the efficacy of Britain’s aristocrats are called into question when he dares to enter The Lair of the White Worm (1989). The close of the century starts to show its creaking age in the seedy, weary world of Downtown Los Angeles, a world of leather, leopard print and fishnets, and post-Sexual Revolution ennui with Ken’s Crimes of Passion (1984) and Whore (1991). But not without a dash of the old sexual hypocrisy which Ken revels in so deliciously.

Aside from inserting himself into the encroachment of reality TV when he appeared on Big Brother, the twenty-first century is the (Wonder)Land of Might Have Been for dear old Ken. A remake of the 1976 musical version of Alice in Wonderland, with scions of the Recession Pop era Lady Gaga and Rihanna as his top picks for the musical numbers, was in the works in 2010. Daltrey would have made a return as the Mad Hatter and Kathleen Turner as the Red Queen. Alas, Ken left this mortal realm for the Great Phallus In The Sky before this dream could be realised. It is left to us who remain to interpret the historic documents, extracting the gaudy and profane, the willowy and the whimsical, from the archive.

In the issue:

Brett Darling on The Music Lovers (1971)

Carmen Paddock on Lisztomania (1975)

Orla Smith on Altered States (1980)