LISZTOMANIA

Carmen Paddock on the composer as superhero – and supervillain.

Hello, and welcome to the first essay from our summer release, Volume 20: Ken Russell’s History of the World. Here, critic Carmen Paddock talks saving classical music in Lisztomania.

On 23rd July, join us at The Cinema Museum for a rare screening of Crimes of Passion on 16mm, where print copies of the issue will be exclusively available. Tickets are now on sale here.

Differences in tone, structure, and quality aside, the biopic largely follows one of two pathways. The first is faithful, canonical, often hagiographic – a great man or woman defined by their best known or loved qualities, often told through cinematic realism and signifiers of authenticity. The second is more subversive and anti-historical, seeking an alternate reading or new interpretation of familiar facts and faces; sometimes, these hint at deeper truths about how and why a legend is created. With cinema being one of the most accessible artistic mediums of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, these retellings go far – arguably further than history books – in shaping common understandings of their hallowed subjects.

Ken Russell’s Lisztomania (1975), a heavily stylised and fictionalised biopic of Hungarian composer and concert pianist Franz Liszt, takes the latter “revisionist” biopic stylings and applies it to the former “canonical” themes. The resulting film – as gonzo and blatantly ahistorical as it is, plays straight into popular perceptions of its primary and supporting subjects, taking those to the extreme rather than dissecting, subverting, or otherwise reworking them. History, classical music, and perhaps even Franz Liszt, have never been this cool.

The historical Franz Liszt carefully cultivated his own image and legend in the imagination of his adoring fans, scandalised critics, and musical peers. Russell picks up where Liszt left off, exploring and exploiting art’s power in the cultural imagination to make a myth out of a mortal. To this end, Russell filters Franz Liszt through the visual and audio signifiers of glam rock godhood (Russell and star Roger Daltry, of The Who, were fresh off Tommy, another psychedelic, fantastical musical retelling blending modern and classical modes, released earlier in 1975).

In broad strokes, it is true. Liszt was a prolific composer and arranger of his fellow composers’ works, a concert pianist who turned the piano sideways so his adoring (largely female) audience could see his profile, a playboy and heartthrob who left a string of broken marriages and illegitimate children across Europe, and finally a late-in-life Abbé whose Catholic faith redeemed his soul in the eyes of society. But in Lisztomania, every facet of this journey is exaggerated and translated into the vernacular of 1970s stardom, augmented through Daltry’s stunt casting and Liszt’s signature instruments: the piano and the phallus.

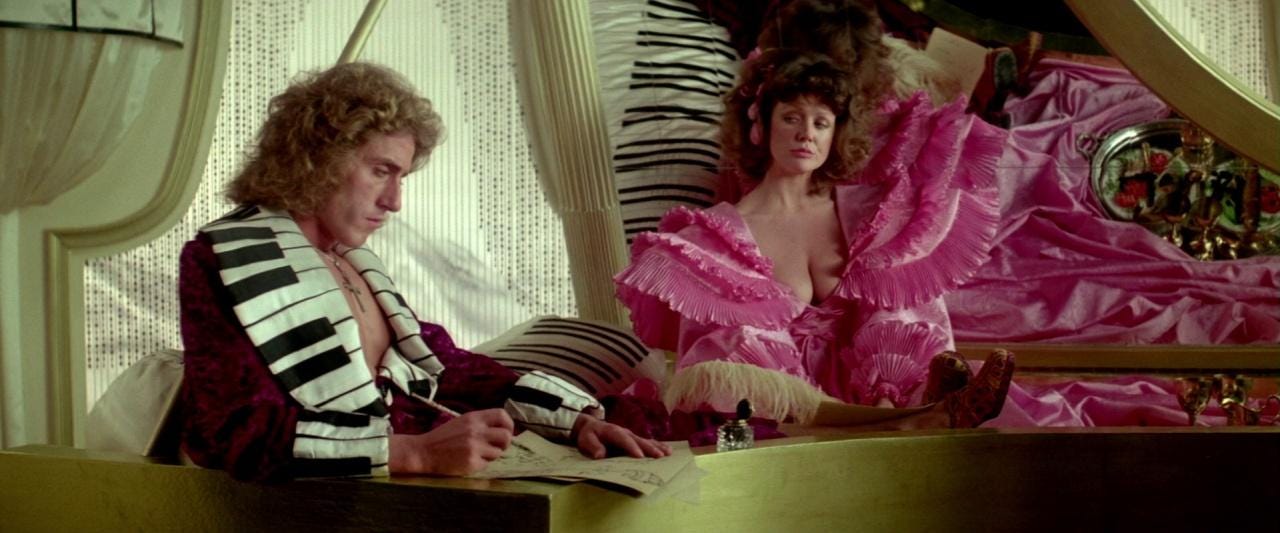

The film opens with him kissing the breasts of his lover Marie d’Agoult to a metronome’s tempo that she continually increases; then (still nude) he loses a swordfight to her husband and is imprisoned inside a piano set on train tracks – a recurring anxiety dream throughout Lisztomania. Hordes of teenage girls are kept at bay from his dressing room by a roadie in jeans and a tight “band” t-shirt. He writes music on his piano desk-slash-bed, wearing a key-trimmed robe, with a marble grand piano silhouette carved above his fireplace. When he goes on tour to Russia, Princess Carolyn (a fictitious figure) and her ladies-in-waiting arouse his genius – and gigantic penis – in a song-and-dance routine. When that too turns out to be a castration-anxiety nightmare, Liszt begins to consider holy-ish vows and the straight and narrow. Cue the Pope (Ringo Starr) in robes covered, not with saints, but with pictures of Judy Garland, sending Liszt on an exorcism mission to save Europe, music, and the Catholic Church.

As Starr’s presence and iconography of Hollywood indicate, Liszt is not the only historical figure reduced to and amplified by his signifiers. After the aforementioned swashbuckling fight and dream of death by adultery and piano, Russell moves the action to Liszt’s chaotic pre-concert dressing suite swarmed by a host of pre-eminent 19th-century romantic composers. Brahms is boring, Mendelssohn pragmatic, and Chopin sadly simping for George Sand. These are incomplete and, in many cases, inaccurate caricatures, but they are based in rumours perpetuated in their own time (and sometimes by each other – according to popular account, Liszt and Chopin both fancied concert pianist Marie Pleyel, and the two composers fell out after Liszt and Pleyel used Chopin’s apartment for a rendez-vous when the latter was out of town. Sadly, this episode does not appear in Lisztomania).

And then there is Richard Wagner – “Satan himself”, as the Pope calls him and charges Liszt to cast him out. He makes his appearance in a sailor suit and a chronologically improbable but very funny Nietzche cap, seeking an audience with Liszt to promote his opera Rienzi amidst the dressing room fracas. Then, in a kaleidoscope of fact and fiction, Wagner anti-semitically insults Mendelssohn (true), gets involved in the Dresden uprising (true), reveals himself as a vampire (false, probably), steals Liszt and d’Agoult’s daughter Cosima away from her husband Hans von Bülow (true), and becomes a proto-Nazi mad scientist prosthelytising to children in Superman spandex and Frankensteining a Siegfried-coded Übermensch into being (both counts false, but not spiritually so).

The epic showdowns at the film’s climax expound on the heightened Liszt and Wagner Russell has cast as saviour and scoundrel. Liszt first kills Wagner with a flame-thrower piano – his signifier becoming his superpower, rather than his doom, as it was in his nightmares – but can only finally defeat the zombified Wagner / Hitler through the power of love: more specifically, a rocket (phallus?) powered by his mistresses and a repentant Cosima. Flying away, Liszt sings that he has found “peace at last” before the credits roll.

In this, Russell imagines a world where composers are supervillains and superheroes damning and redeeming the world, transcending their historical caricatures by fully committing to them. His is the history of the popular imagination: an uproarious send-up and celebration for those in the know, and a delirious fantasy for viewers who have never heard the name Franz Liszt. Furthermore, his collection of aesthetic calling cards imagines a world where classical music is unabashedly cool, its stars greeted like rock gods with screaming fans. “Truth is stranger than fiction - we’ve kept going for two thousand years on that one,” Starr’s Pope says. By taking Liszt’s legend to the extreme and wrapping it in pop trappings, Russell came tantalisingly close to giving classical music its brat summer 50 years ago. But when will classical music have another brat summer?

On 6 January 2025, the podcast Thrilled to Announce released an episode entitled opera is undead, the “it” girl will save us. Amongst discussions of the role of the critic in opera, hosts Charlotte Jackson and Perri di Christina discuss how opera has lacked an inarguably cool figurehead since perhaps Maria Callas. Looking at the wider classical music industry, there is certainly no one at Callas’ or Liszt’s level today. There is still brilliant, inventive, genre-redefining work happening in the sphere, but its glory days are implied to be far behind us. Concert halls are lined with busts and statues of great composers – Liszt’s dressing room in stone. In brief, classical music might be deeply uncool.

Of course, cool is a relative term and not a vital quality for good art. But when Russell harnesses these larger-than-life legends to bridge the cool gap between classical and pop music, he takes these gods off their pedestals and counterintuitively amplifies their power. Indeed, the holy water Liszt tricks Wagner into drinking before the flamethrowing piano comes out has no effect; religion is nothing in the face of music, and Liszt must believe in his own gifts – believe in them as much as Wagner has always done – to ultimately come out on top, singing his way into his own mythology.